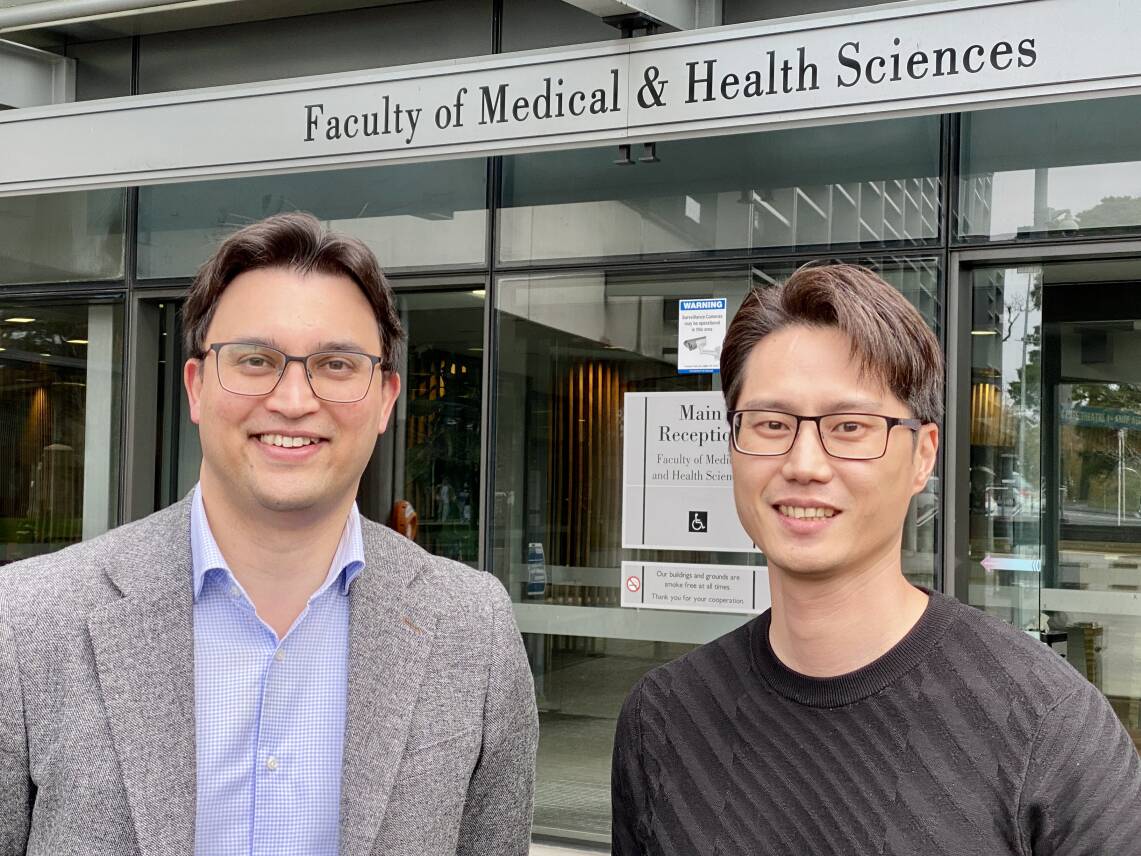

The call will come from neurosurgeon Dr Jason Correia. Dr Correia will be intensely focused on his work removing a brain tumour but will still make time to alert Dr Park that some incredibly precious tissue is about to be made available for research.

These two have collaborated to devise a time-sensitive plan to keep the tissue alive. It involves one of Dr Park’s team arriving at the operating theatre to collect the brain tissue in a pre-prepared vial and then running from the hospital back to the medical school to transfer it to a special medium to ensure this valuable gift doesn’t die.

A few minutes of running can provide a month’s critical research, and relies on the amazing selflessness of patients who have brain cancer. “It’s the most precious gift,” says Dr Correia. “We find a high percentage of patients are keen to help even though they know it won’t benefit them directly. They do it because they want to help others in the future.”

Funded by a Neurological Foundation grant of $277,768, Dr Park is looking at the long-term side effects of radiation on the brain – something that he knows is of concern to patients. He says his research won’t solve problems directly, but will shed light on processes that have, as yet, remained a mystery.

This current research builds on the groundwork laid by a broader team whose innovative efforts began three and a half decades ago.

EARLY BEGINNINGS

In 1988, the University of Auckland’s Professor Mike Dragunow and Distinguished Professor Sir Richard Faull collaborated with neurosurgeon Dr Ed Mee to start collecting brain tissue for research from Auckland City Hospital. Every study since then has been led by Professor Dragunow, while neurosurgeons including Dr Mee, Dr Correia, Dr Patrick Schweder, Dr Andrew Law, Dr Peter Heppner, Dr Chien Kow and many others, along with neuroscientists, technicians and neurosurgery nurses, have contributed to the ongoing work.

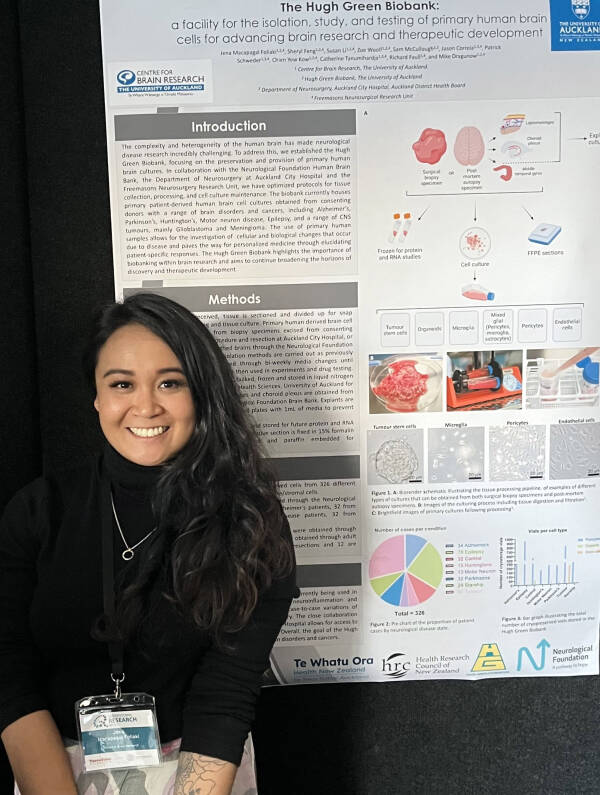

The collection of brain tissue (including brain tumour tissue) and research using it is largely funded through the Centre for Brain Research’s Hugh Green Biobank, founded and directed by Professor Dragunow (above). Professor Dragunow received an amazingly generous philanthropic grant of $13.8 million from the Hugh Green Foundation to run the biobank in perpetuity. This allows early to mid-career researchers, like Dr Park, to get funding from organisations like the Neurological Foundation to conduct research projects that benefit patients, while establishing their independent research programmes.

The Centre for Brain Research Freemasons Neurosurgery Research Unit was founded by Professor Dragunow and is co-led with Dr Correia. Through the Freemasons Neurosurgery Research Unit, a senior neurosurgery nurse (position shared between Catherine Tanumihardja and Awhina Walters) undertakes the consenting process with the generous patients/donors at Auckland City Hospital and looks after patient details and other clinical aspects of the study. Various research technicians and the Hugh Green Biobank manager Dr Jena Macapagal Foliaki (below), who undertook a PhD with Dr Park and Professor Dragunow, liaise directly with the nurse. They collect all the tissue and undertake the culturing needed to generate various human brain cells and brain cancer cells for research and drug testing.

(As well as the Freemasons and Hugh Green foundations, the Health Research Council has been a generous supporter in this area. Professor Dragunow is also Director, Health Research Council Programme Grant – Neurovascular pathology in human degenerative disorders.)

So far, close to 300 tumour tissue samples are stored in the Hugh Green Biobank. Tumour tissue from one patient may be used by many groups in numerous, often collaborative, research projects. Some are also fixed and frozen for future projects.

DELICATE CONVERSATIONS

Dr Correia’s team is responsible for asking patients for permission to use small amounts of their removed tumour and brain tissue for research. He says it’s not an easy conversation given it happens at a time when these patients are dealing with a devastating diagnosis. It’s made very clear that it’s voluntary, and cultural sensitivities are always taken into account.

The bulk of the removed tumour is sent to the pathology lab to confirm the cancer diagnosis. A small amount is provided to the Hugh Green Biobank for Dr Park’s research.

Before this was possible, Dr Park and Dr Correia had to work out how best to preserve the tissue. The problem they faced was that non-diseased brain cells are extremely sensitive to being cut off from the blood supply, and quickly die. They needed to devise a culture medium to keep them alive, and work out the best way to transfer from the operating room to the lab.

“There was nothing out there to guide us,” Dr Park explains. “We had to invent how to do this and it’s exciting because now we’re putting what we found into practice.” Dr Park says he knows of few other places in the world where scientific and surgical teams have forged such successful partnerships.

Their established routine will involve a second trip too. The first one, as described, is a rapid retrieval of non-cancerous tissue that’s been taken en route to the deep-seated tumour. The second trip comes after Dr Correia has then resected the tumour itself which takes more time. Tumour tissue isn’t so sensitive to blood supply loss so the retrieval process doesn’t require such a fast sprint.

RESEARCH TO REDUCE RADIATION DAMAGE

Having access to this tissue has allowed Dr Park to carry out research that’s very important to brain cancer patients. He’s looking at the long-term side effects of radiation on the brain. Radiation oncologists always try their utmost to limit any radiation reaching beyond the tumour itself, but it’s impossible to avoid it altogether, and often, some low-level radiation will affect the surrounding normal brain tissue. The short-term effects of this are well-documented but little is known about the long-term impact, such as radiation-induced cognitive decline and dementia.

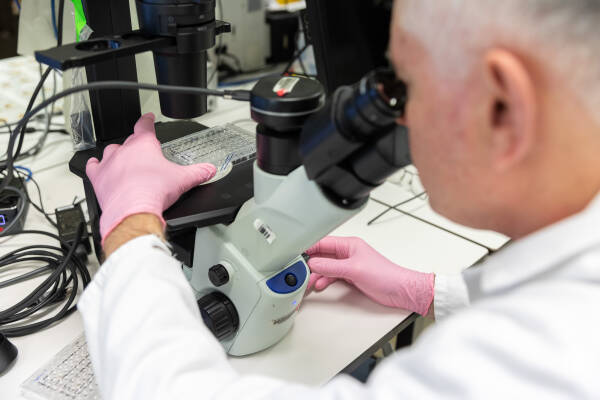

Dr Park applies low-dose radiation to the living human brain tissue and documents changes both in the short-term and over the period of a month. This is roughly as long as they can keep the tissue alive. Dr Park says having this live human brain tissue is a game changer. For the first time, they can investigate the effects of radiation in intact human brain tissue. This provides much more information than would be possible by examining the various cell populations in isolation.

Dr Park knows finding a way to limit radiation damage is important to patients. This was confirmed at a recent national brain tumour conference in New Zealand. The long-term side effects, such as dementia or ataxia (problems with co-ordinating movement) were the subject of many patient questions. Despite being incredibly grateful for surviving the brain tumour, it was clear they had concerns about the negative neurological impacts from radiation therapy.

Dementia is certainly a difficult condition to cope with. It can rob people of their ability to drive, they can lose their balance, or become forgetful, and their character may change. It’s another loss of quality of life.

Interestingly, the research may also have benefits for the study of dementia from other causes. At present, it’s impossible to tell when the decline into dementia actually starts. In contrast, if human brain tissue receives a dose of radiation, the precise starting point is known. This allows researchers to look for the first signs of change.

Dr Park says his research won’t solve problems directly but it will shed light on processes that as yet have remained a mystery. This would allow other researchers to be more specific in their work, for example, if Dr Park finds that there’s a protein change at the transmission site of nerve impulses (the synapse) that could lead to a deterioration in memory, then other researchers could investigate whether any drugs can prevent the change. At the moment, it’s more a discovery approach as researchers have little to guide them on where to focus their efforts.

Both Dr Park and Dr Correia want to thank the Neurological Foundation for supporting their work. Over time, they’ve received several Neurological Foundation grants and scholarships, which they describe as “project enabling and career-defining”. Dr Park currently has a 2-year grant of $277,768.

Their work in improving brain cancer care doesn’t stop there. Dr Park worked with a team of brain tumour researchers and clinicians from across Aotearoa to establish the first national brain tumour Society (NANOS - NZ Aotearoa Neuro-oncology Society), through which they’re currently working towards establishing a national brain cancer registry. The aim is to share research findings and best clinical practice across the country. Individual hospitals do hold information but there has been no national brain tumour database.

The current brain cancer databases only keep basic information, and often only for primary brain cancer. The registry working group believes it would be useful to add data on benign tumours and those that have metastasised from other cancers, and to provide much more detail, such as treatment plans and how effective they are.

Dr Park says the absence of this information “kneecaps New Zealand” when it comes to interest from clinical trial organisers from overseas because it’s impossible to provide the comprehensive data they need.

The work to establish the registry is now in full swing with seed funding from the University of Auckland. This funding allowed Dr Park to hire a full-time national co-ordinator to help lead these efforts. All others involved in getting the framework ready are doing so on a voluntary basis. Dr Park and the NANOS committee (including representatives from each District Health Board) are hoping to raise awareness of this project as they believe it could inform future research, and influence the policies of both the government and Pharmac to best support brain tumour patients and their whānau.